Managing farm nitrogen

Pasture plants need nitrogen for healthy leaf growth. However, when there’s too much nitrogen it can pollute our streams, rivers and ground water. High levels of nitrogen in our water can lead to nuisance growths of water plants and algal blooms (including slimes in rivers). Find out where nitrogen comes from, how it is cycled in the environment and how to best manage nitrogen on your farm.

Where nitrogen comes from

On the farm, nitrogen is supplied to the soil from:

- fertiliser

- stock urine

- effluent irrigated to land

- nitrogen fixing bacteria - living in ‘nodules’ on the roots of legumes, such as clover.

Clover – a natural source of nitrogen

Healthy clover is a low cost natural source of nitrogen. The bacteria living in the ‘nodules’ on the roots of clover convert nitrogen from the air to a form that can be used by plants.

Check to see if your clover is healthy by looking at the roots. Healthy clover has deep roots with nodules about the size of a match head. The inside of the nodules range from pink to blood red when healthy and functioning properly.

Look after your clover by:

- making sure grasses don’t over-shadow clover in spring and winter

- avoiding pugging in winter – the growing tips of clover are easily damaged

- sowing clover seed shallower than grass seed – discuss planting options with your contractor

- targeting your fertiliser to enhance clover

- seeking advice about weed control

The nitrogen cycle

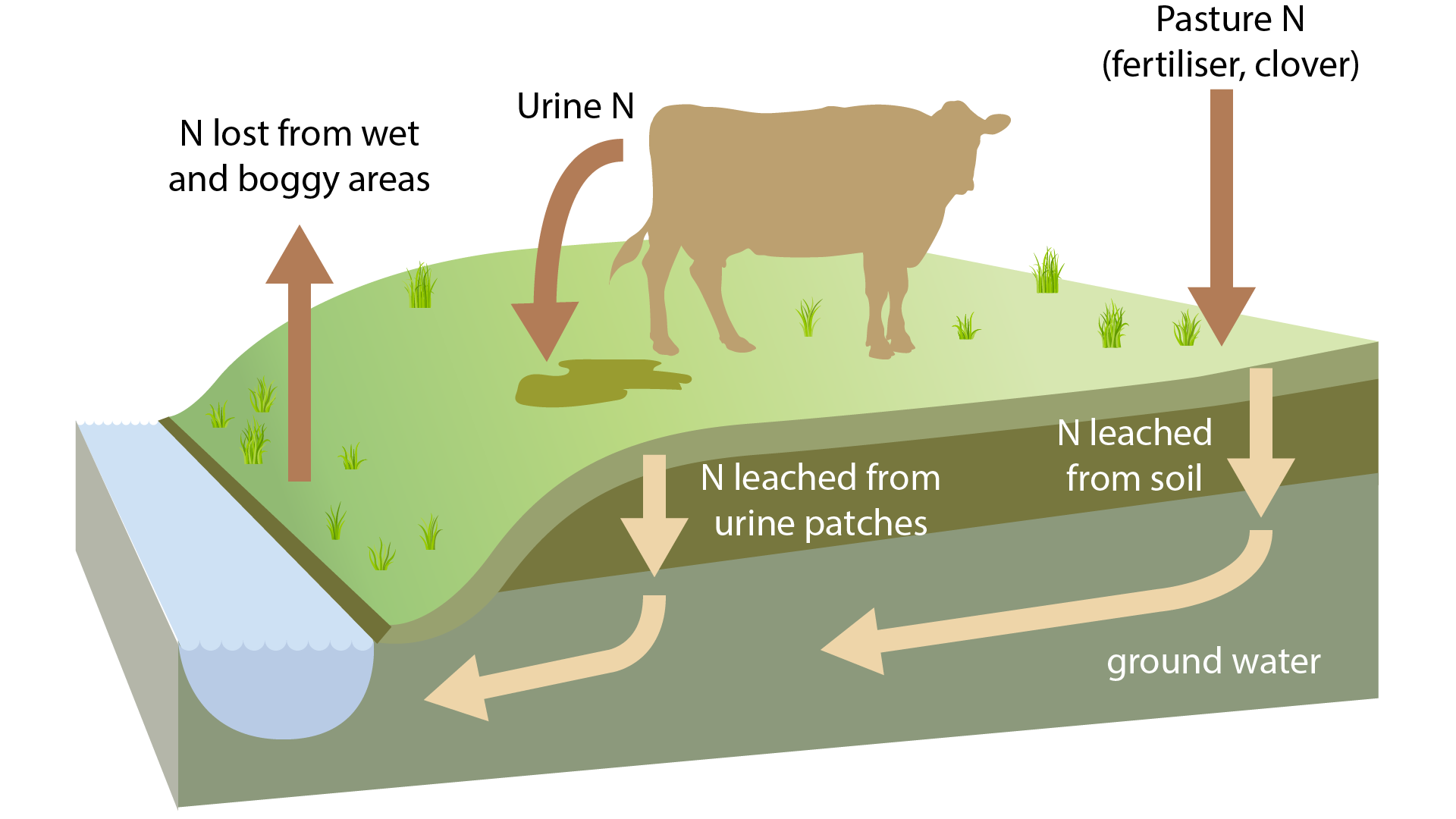

Nitrogen is cycled between the soil, pasture plants, stock and the atmosphere. When stock eat pasture plants (such as grasses and clover) they are consuming nitrogen. Stock then deposit nitrogen-rich urine back onto the paddock (see diagram below).

Patches of urine contain much more nitrogen than plants can take up. The concentration is about the same as applying about 1000 kilograms of nitrogen per hectare. Soils can’t store this much nitrogen so most of it ends up leaching down through the soil into ground water. Some nitrogen will also be released back into the air as gas.

The pie charts below give you a rough idea what happens to nitrogen on a typical dairy or drystock farm. The pale green area on each graph is the amount of nitrogen going off the farm as product.

What happens to nitrogen on a typical dairy or drystock farm

Where nitrogen goes on dairy farms

Where nitrogen goes on dairy farms

Where nitrogen goes on drystock farms

Where nitrogen goes on drystock farms

How nitrogen affects waterways

Over 90 percent of streams have moderate or high levels of nitrogen in intensively farmed catchments. Find out how Waikato Regional Council measure water quality. Check out the water quality of streams and rivers in your area.

Up to one third of the nitrogen entering soils on intensive farms may end up leaching down through the soil into ground water. This nitrogen-rich ground water will eventually flow into and pollute drains, streams, lakes and coastal water. High levels of nitrogen encourages nuisance weed and algae growth, which:

- ‘chokes’ waterways and blocks water intakes

- affects stream life , for example, by changing the stream environment

- makes water unpleasant for swimming and drinking

- affects harbours and estuaries, for example, by encouraging the growth of algae and mangroves.

High levels of nitrogen in sources of drinking water also affects people’s health. Over 40 percent of shallow ground water in the Hamilton Basin is unsuitable for drinking because of nitrogen contamination. Find out more about nitrate contamination of ground water.

The table below shows the percentage of nitrogen entering the Waikato, Piako and Waihou rivers from:

- agriculture

- point sources - such as, sewage works and factory discharges

- background levels - such as from undeveloped land.

|

Source |

Waikato River (1990-96 data) |

Piako River (1993-97 data) |

Waihou River (1993-97 data) |

|

Agriculture |

45 to 65% |

85% |

75% |

|

Point sources |

15% |

4% |

10% |

|

Background levels |

20 to 40% |

11% |

15% |

Reducing the effects of nitrogen leaching

Reduce the amount of nitrogen leaching from your pasture and reduce its effect on farm waterways by:

- timing your fertiliser application to avoid times when plant uptake of nitrogen will be low, for example, when there are saturated soils, heavy rain and low soil temperatures

- applying nitrogen fertiliser in split dressings, rather than all at once, so pasture can use it for growth (reduces the amount lost to leaching and is more cost effective)

- making sure you are irrigating farm dairy effluent to a large enough area

- adjusting your fertiliser policy for effluent irrigated areas to account for the nutrient value of effluent

- using fenced wetlands and well-managed open drains as nutrient traps, where nitrogen can be converted to a gas and released to the air.

Remember that many pasture soils in the Waikato Region are over-fertilised. Around 30 percent of North Island dairy farms have twice the level of soil nutrients needed for pasture growth. Have a go at doing a simple nutrient budget for your farm using one or more of our online worksheets:

Where can I find out more?

Find out how Waikato Regional Council monitor:

- nitrogen leaching and nitrogen in runoff

- nitrate contamination of ground water

- nitrogen losses from land.

Find out more about estuary monitoring and algal blooms in the Waikato River.

Check out the NZ Fertiliser Manufacturers' Research Association Code of Practice for Fertiliser Use.

The Wise Use of N Fertiliser on Hill Country Project aims to encourage nitrogen use practices that enhance long-term farm profitability whilst minimising potential adverse environmental effects. This project is run by AgResearch and funded by the MAF SFF, Fert Research, Meat and Wool NZ, Ravensdown Co-op Ltd, Ballance Agri-Nutrients Ltd and PGGRC.

Find out about using poplars and willows to reduce the amount of nitrate leaching from dairy shed effluent from HortResearch.

To ask for help or report a problem, contact us

Tell us how we can improve the information on this page. (optional)